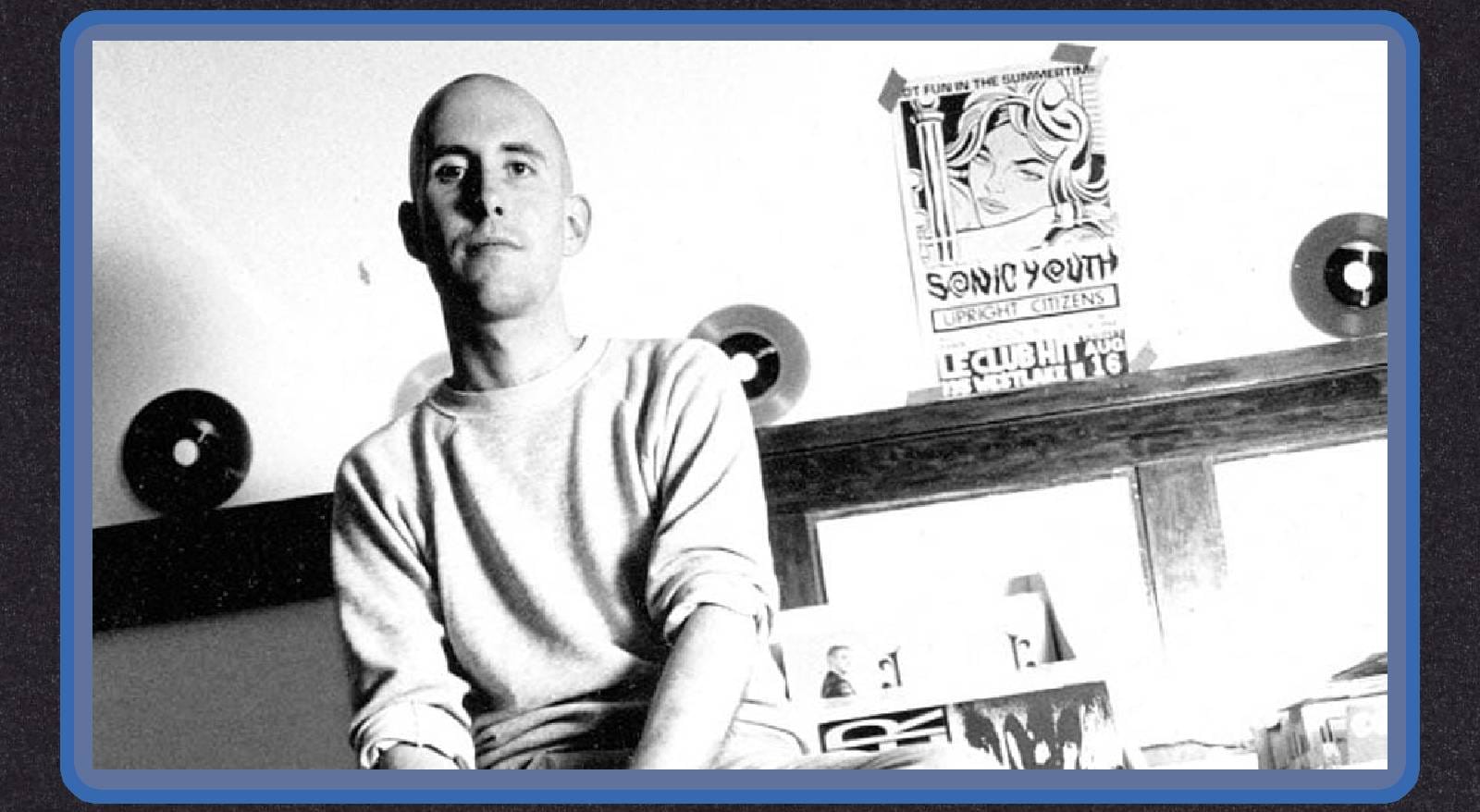

Seek and Consume: On Sub Pop, Bruce Pavitt and Eternal Music Criticism

Why reading Bruce Pavitt's Sub Pop writing from the 1980s made me feel optimistic about the value of music criticism today.

I think the mark of a great music critic is someone who makes you need to listen to everything they like, and never want to hear anything they hate, even if it’s actually something you might enjoy. By that metric, Bruce Pavitt is one of the greatest music critics I’ve ever read.

I just finished reading Sub Pop USA: The Subterranean Pop Music Anthology, 1980-1988, which bundles together all of Pavitt’s Sub Pop zines and Rocket newspaper columns that he wrote before he fully committed to the label that broke grunge and changed the course of rock music forever. As someone who grew up in the 2000s and came of music-nerd age in the 2010s, Sub Pop the label has always been a legacy institution to me, a pillar of history that's synonymous with a place in time that predated my birth. Sure, they're still an active business who’ve released music by some of my favorite modern bands, and right now (spring 2023), they're on a serious hot streak again; Sweeping Promises, Bully, Waterbaby and Debby Friday are four wildly different acts who’ve each dropped some stellar material this year.

However, Pavitt’s writing from 40 years ago was never relayed to me as essential reading material. Sadly, I think a lot of that foundational zine writing from the late 70s through the end of the 80s has been memory-holed by the decades of digital music criticism that’s piled up on top of it. While there’re niche communities who still actively herald the scribes of eons past (hardcore, for instance, but even that's beginning to fade as the genre’s culture morphs yet again — an essay for another time), I don’t really think that my specific age group (people now in their mid-to-late-twenties) really have much of an attachment to the bounty of independent music writing that established the indie-rock bedrock we’re still standing on today.

For most of my life, I’ve been as guilty as any of my peers who implicitly treat Pitchfork’s inception in the late 90s — and with it, the beginning of the blog era — as the starting point for contemporary music journalism. Anything earlier (I.E. print media) is simply not easily accessible (if accessible at all!) on the internet, and so a lot of that stuff — the peak Spin years, all the Melody Maker shit, the best NME eras, stuff like Q, Blender, The Face, not to mention all the iconic mags from the 60s and 70s — just doesn’t make its way into the music journalism dialogue of today. If you live your life on the internet, listen to all of your music on the internet, read all of your media on the internet, it’s really easy to just ignore, out of convenience, anything that predates the internet. It might be one of the saddest, most toxic forms of brain rot that social media’s now-or-nothing continuum has wrought upon our cultural identity.

Let me be clear: so much of the music writing from the old days is, in fact, dogshit that's not worth remembering, just as so much of the music criticism that's been digitally published in the period since Pitchfork’s Kid A review is also, in fact, unreadable dreck. Lotta bad writing out there, always has been. Pavitt’s writing, on the other hand, holds up remarkably well, and I think any contemporary music writer who considers themselves a critic could benefit from reading the monthly column he churned out in tandem with indie music’s coming-of-age throughout the 80s.

Most of his columns began with some preamble about a show he recently saw, a hot scene he’s been hip to, or a label who’ve been putting out a string of notable releases. He might spend a few grafs waxing on that, and then dive into a series of 10-15 album reviews, culminating with either a list of his favorites of that month, or an inventory of cool zines/labels/venues/radio stations he urges his readers to check out. His writing in those intros is often personal and/or humorous, and usually references friends of his in the PNW music scene. But for the reviews, he typically zeroes in on a bit of context about the release and then offers a take. No long setups, no loquacious allegories, and no flowery, ivy league cha-chings of 25-cent words. Here’s the record, and here’s what I think about it. Boom.

It’s in those review blurbs where his voice really resonates with me. Efficient, kinetic, persuasive, funny, curious and brutally honest, Pavitt was a master at transmitting a nuanced take on a record in sometimes less than 50 words. His writing usually focuses on the content of the music, with very little frivolous commentary on the personality or time spent weaving the artist’s own self-professed narrative into these calls of quality. It’s a refreshingly concise and straightforward approach that, I think, would resonate with today’s readers, when we all suffer from paper-thin attention spans and are so inundated with choice that we need a snappy, confident voice to help guide us through the sea of options.

Pavitt had an impressively thorough understanding of pop music history by the time he started writing these things as a young twenty-something, and he was seemingly knowledgeable — or could at least present as knowledgeable — about all sorts of other genres, from primitive country and blues, to experimental, jazz, novelty music and more. I like that he didn’t wield his dense vocabulary to isolate readers who didn’t have the same background, but to encourage them to dig beyond their comfort zones and try some of the truly weird, outsider shit that he reviewed right alongside the latest hardcore and indie-pop LPs.

Compared to early Pitchfork reviews, for instance (or Lester Bangs’ work, for that matter), Pavitt doesn’t ramble, is rarely snarky and approaches most of the material in good faith. After reading hundreds of his plucky little blurbs, I still found it difficult to predict what he would like and what he would meh at, which made this compendium of writings interesting to flip through all at once, even though the individual columns were never written to be part of a linear narrative. The brevity of his prose really struck me again and again. Here’s his blurb on Sonic Youth’s Kill Yr Idols 12-inch from his July 1984 Rocket column.

Unbridled hipness from one of NYC’s most creative bands. They’ve taken the best from the Confusion is Sex LP, added three intense new tracks, and put it all on a kick-ass 12” at 45 rpm. This art/punk outfit from the Lower East Side literally redefines bass, drums and guitar — everything’s wobbling and off the edge. The production is excellent, too, lots of clarity but very raw. Seek and consume.

Aside from the fact that he was one thousand percent correct in identifying the revolutionary vision of Sonic Youth years before they’d truly take off, his writing on them is just so succinct and active. “Unbridled hipness” is a hilarious way of conveying SY’s pretentiousness, setting off alarms of skepticism or pavlovian salivary glands depending on who’s reading. But then every subsequent observation conveys exactly what makes this record a must-have, from describing its sound and setting its place in the country’s network of scenes to ordering his readers to “seek and consume” — all in a brisk 70 words! That's a lot harder to do than it reads, and he did it ad infinitum. Impressive.

Sure, Robert Christgau was also a master of that style, but for the period of music that Pavitt covered, I think his taste was better and easier to relate to. He didn’t demand that artists prove themselves before he threw his whole weight behind them. He was just as likely to laud some random garage-pop 7” from Boston as he was the early Sonic Youth material. He also wasn’t afraid to turn on a band when he thought they attempted a new direction that failed, or issued a record that too closely rehashed their previous masterpiece. By the end of Sub Pop’s existence as a music column, his focus was obviously on platforming the bursting Seattle scene he had been tracking for years prior, which ultimately led to Sub Pop’s transition from critical body to commercial record label.

In his present-day commentary littered throughout the book, Pavitt wrestles with the regret he now feels for hurting artist’s feelings (and likely affecting their careers, given the influence of his words) with negative reviews. Obviously, doing away with trashing bands proved to be a very lucrative move for Pavitt during his next phase in the music business, and some of that good fortune has probably colored his feelings about his strongly-worded opinions toward other artists. That's too bad, because I think his bullshit detector was one of his greatest strengths, and it’s especially useful to someone like me who’s taking in all of this musical history several decades after the fact. It’d take multiple lifetimes to retrospectively digest all the scenes and sounds Pavitt was hearing in real-time, so the fact that he considered a solid 40 percent of the music he covered to be mediocre, flawed or downright awful provides a handy roadmap for people of my generation and younger to follow along with. If he only wrote about stuff he loved, his writing wouldn’t have the same historical dimensions, and I think this book would’ve been a lot more draining to consume if I felt like I had to stop after every blurb to hear what he was raving about.

I’m very loud about the importance of negative criticism, but I’m mostly just a proponent of honest criticism. Pavitt shows exactly how writers can make room for over-the-moon, effusive enthusiasm and flagrant disappointment. When he loved something, you could practically feel his excitement buzzing off the page. With pithy call-to-actions like “buy it or die,” and gushing, repetitious phrases like, “love, love, love this,” he never reigned in his eagerness about something he liked in service of a stuffy professional veneer. He was emphatic with every opinion he dolled out, and he got it right so many times that I found myself shaking my head at certain points just to marvel at his foresight.

He saw the Seattle explosion coming as a critic and scenester years before it happened, and he used his vantage point in the PNW to champion bands that would go on to become legendary, if still underrated (Melvins, Wipers, Beat Happening, U-Men). National bands, too, from the noise-rock lunacy of the Butthole Surfers, Killdozer and Big Black; the swaggering punk-metal of Dinosaur Jr. (when they were just called Dinosaur); the forward-thinking genius of Run D.M.C. and Ice-T; the eccentric charms of Half-Japanese’s Jad Fair and electrical wizardry of future grunge producer Steve Fisk; the blistering highs and depressing lows of Black Flag’s groundbreaking, frustrating catalog; and which albums on prolific labels like SST, Touch and Go, Twintone, etc. were worth nabbing. The albums he really hypes are so often the most revered albums of the 1980s underground, and seeing him inform and identify that canon through his column is just plain fun.

Pavitt wasn’t perfect, though. His harsh criticisms of blatantly sexist bands weren’t always consistent, as he excused the crude, violent lyrics of groups like Swans, G.G. Allin and Pussy Galore while making moral slashes at nasty hardcore bands with the same humor, simply because he didn’t think they were clever or aesthetically pleasing in their approach. It wasn’t so much the content of the messages, but how credible of an artist the man delivering them was in Pavitt’s eye. I cringed reading him laud the provocative rape songs of Swans’ Michael Gira, interpreting the New York noise-rock pioneer as a fearless confronter of brutal realities, expressed from the impartial safety of artist-dom. Decades later, Gira would be credibly accused of raping a woman, savagely undermining whatever thought experiments he was putting forth on Swans’ 1984 Young God EP (featuring the ditty "Raping a Slave"), which Pavitt revered in many of his columns. Similarly, Big Black’s Steve Albini would later be rightly chastised for his careless edgelord ramblings that he thinly masked as innocent gallows humor, humor that Pavitt applauded while turning his nose at “fascist” hardcore or metal bands who sang about the same subjects in less eloquent terms.

While he posited himself as an enlightened, feminist, anti-racist liberal, and his early zines had a strident political message that was fiercely anti-corporate and nominally anti-misogynist, he was still a white man writing about music in the 1980s. I will say, there were very few passages that would actually catch him flack on Twitter today, other than the stray fleck of jive appropriation while covering a funk or soul artist (cringe), and the occasional eyebrow-raising characterization of a female subject. Like many men, he could write boyishly about women, either awkwardly fawning over them or falling back on needless nit-picks when their music didn’t strike his fancy. Even so, many of the old Pitchfork reviews are more proudly offensive than anything Pavitt ever typed, which again makes his body of work still feel surprisingly resonant all these years later.

Without getting too deep in the weeds here, I think the only type of writing that's going to have any value after AI tech takes over is writing that's undeniably human. Writing that offers something a computer program never could, which is a human impression on a piece of music. An opinion, an aside, a vivid documentation of a real-life event — something usefully corporeal, tangible, emotionally relatable in a digital landscape where algorithms will be trying to spoon-feed you soulless regurgitations of robotic Wikipedia entries at every click. Pavitt’s stripped-down format and unambiguous candor is the kind of music writing that, I think, will outlive the machine takeover. Read it or die.